A promising breakthrough in liquid condensate compartmentalisation

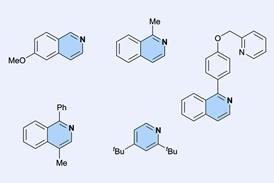

Tears are RNA solvent droplets that could help engineer new functions into bacteria

The Breakthrough Prizes, cannily announced just weeks before the Nobels, don’t yet attract the attention and speculation the Swedish prizes enjoy. But at $3 million (£2.6 million) apiece, they are more lucrative for the winners. The prizes are for three disciplines – fundamental physics, mathematics and life sciences – and it’s fair to say that one of the topics rewarded this year in the last of these categories was on no one’s radar 20 years ago. It went to Anthony Hyman of the Max Planck Institute for Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics in Dresden, Germany, and his former postdoc Clifford Brangwynne, now at Princeton University, US, for their discovery of the importance of liquid–liquid phase separation in cells.

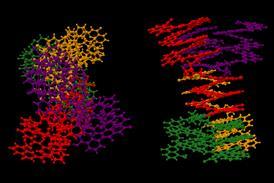

In 2009 the duo reported that structures called P granules in germ cells of the nematode worm Caenorhabditis elegans are liquid droplets containing proteins and RNA molecules that have separated from the cytoplasm in a classic phase transition [1]. They closely resemble structures called RNP stress granules, made from RNA and RNA-binding proteins (RNABPs). RNP granules form in cells in response to stress and have a variety of roles in metabolism, memory and development. Brangwynne also found that the nucleolus of eukaryotic cells – the region in the cell nucleus where protein-manufacturing ribosomes are made – also bears the hallmarks of a liquid droplet.