How rubber is bouncing back

From their colonial roots to future alternatives, Kit Chapman looks at the chemistry of natural elastomers

Most rubber comes from Hevea brasiliensis, the Pará rubber tree, which produces a thick latex in specialised cells, laticifers, to protect against insects. This is rich in elastomers, particularly cis-1,4-polyisoprene, along with a mix of proteins, fatty acids and resins. Rubber was harvested by the Aztec and Maya, who used latex to make sports balls and storage containers. But it wasn’t until the American chemist Charles Goodyear discovered vulcanisation in 1839 that the material showed its full potential.

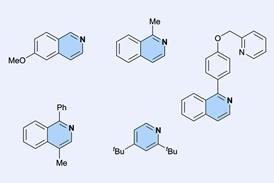

An estimated 70% of natural rubber production is used in tyre compounds, it has countless other uses, from ‘elastic’ fibres in clothing and glue in textile industries to protective gloves, condoms and rubber bands. Although synthetic rubbers exist, they are a poor substitute for the real thing. There are two leading contenders for plants that produce a natural rubber alternative.